Give a kidney, get a kidney: The magic of the national kidney swap network

Mother and son benefit from kidney paired exchange and save the life of someone else

November 07, 2024 From left to right: Drew Barefoot, Jessica Corey, Kip Barefoot, and Lana Castle participated in a kidney-swap after two viable donors were not able to match with their original receipts. (Contributed image)

From left to right: Drew Barefoot, Jessica Corey, Kip Barefoot, and Lana Castle participated in a kidney-swap after two viable donors were not able to match with their original receipts. (Contributed image)

By Jeff Kelley

What if you wanted to donate your kidney to a friend or family member in need, but your blood type or other factors aren't a match for transplant?

Kip Barefoot and her son Drew know the feeling.

Years ago, she was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease (CKD), putting her at high risk for both kidney failure and heart disease. The damage to Kip's kidneys was irreversible, requiring time-intensive dialysis care to survive — or a new kidney to improve her chances of long-term survival and improve her quality of life. Her son was a healthy, ready, and willing living donor.

“I don't need two kidneys. We can all donate organs and take care of the ones we love, because we have spare parts,” Drew said. But their blood types and biomarkers “fought one another,” Kip said. Doctors explained that less than 2% of people were compatible with Kip due to the antibodies in her system that would attack most foreign tissues.

Even if you aren't a match for the person you are testing for, open up to donating it to someone else, because you don't know whose life you're going to change.

Kip Barefoot, kidney transplant recipient and VCU Health patient

Despite the pair's incompatibility, the VCU Health Hume-Lee Transplant Center team presented the Barefoots an alternative option: If Drew was willing to donate his kidney, his organ would be put into a national database of other mismatched donor-recipient pairs, where he would save a stranger's life and his mom would be able to find a match from someone else. In doing so, they skip the 96,000-person line that is the national waiting list for a kidney.

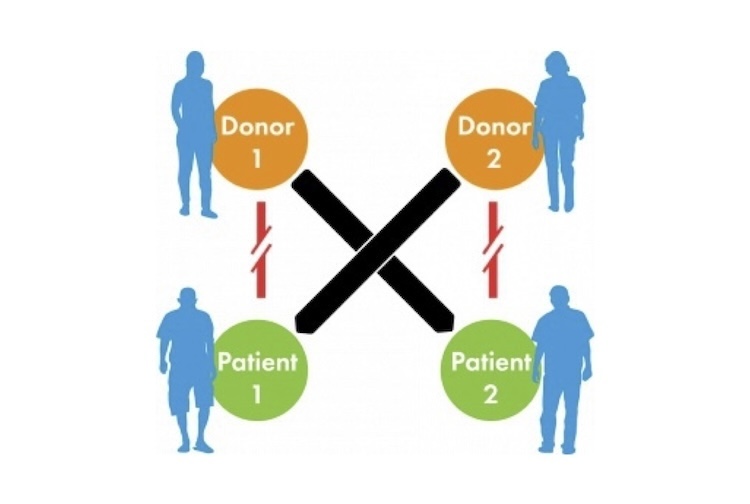

Known as a kidney paired donation or “kidney swap,” incompatible pairs who agree to the swap process gain unique access to a network of thousands of other mismatched donors and recipients. With his donation, she was all but guaranteed a kidney.

“We knew it was going to happen, but it was just like, at what point? How complicated would the chain get?” Drew explained. “There was no hesitation, it was just one step at a time.”

How paired organ donations can save multiple lives

Hume-Lee Transplant Center transplants more than 300 kidneys a year. Of those, about 40 organs come from living donors, while the rest come from deceased patients.

Of those 40 living donors, 25% are from a paired kidney exchange.

“If you look at transplant centers that do a high number of living donor surgeries, they all also do a high number of swaps,” said Dhiren Kumar, M.D., Hume-Lee's medical director of living kidney donation and Kip's transplant nephrologist.

Organs from living donors are associated with fewer complications than deceased-donor transplants and the donor organ offers a longer survival.

“In the last few years, our focus has been to increase the number of swaps, which is a way to save more lives and increase access to living donor kidney transplants for our patients,” Kumar said.

The choice to enter the kidney paired exchange program is entirely on the donor and recipient.

“Most living donors are coming to us for altruistic reasons, and they readily sign up to give their organ to anyone in need,” Kumar said. “Ninety-nine percent of people who are willing to donate an organ agree to participate in a swap if needed.”

From there, the donor kidney is entered into a database with the Alliance for Paired Kidney Donation. A computer algorithm works its magic to match pairs.

The matching process involves close coordination between transplant centers, including sharing medical records, discussing cases and logistical planning. VCU Health aims to reduce barriers to donation, including financial and logistical challenges. Programs offer wage reimbursement, insurance, and travel assistance to donors and recipients. Whether at VCU Health or elsewhere, living donors are never charged a penny for transplant.

“Removing these barriers is key to increasing living donor transplants,” Kumar said.

How it worked for Kip and Drew

Paired exchanges can often become chains-long of people. But in the case of Kip and Drew, theirs was a relatively simple “direct” swap: another incompatible donor-recipient pair matched them, and the four swapped.

A national database contains lists of mismatched donor-recipient pairs who are willing to swap with another willing duo. (Contributed image)

On March 6, 2023, Drew's kidney was removed at VCU Health by robotic surgeon Seung Duk Lee, M.D. With robotic surgery, Drew experienced many benefits - smaller incisions, less bleeding, less pain and a faster recovery. His kidney was driven to Wake Forest in Winston-Salem, N.C., where it was transplanted into a woman in her mid-30s with whom he matched, Jessica Corey.

At Wake Forest with Jessica was her longtime family friend and incompatible living donor, Lana Castle. Lana matched Kip. Lana's kidney was removed at Wake and driven to Richmond; when the kidney hit Petersburg, about a half hour south of Richmond, Kip was taken to the operating room where she was transplanted by surgeons Adrian Cotterell, M.D. and Amit Sharma, M.D.

The surgery took place on Monday, and Drew was home by Wednesday. “I wasn't skipping out of there by any stretch, but I was stable enough,” Drew said.

A special visit to Kip's tearoom

Drew and his wife Dana have two young children. His family factored into his decision to donate, but not in terms of risking his life - living donation doesn't change life expectancy - or future issues with only one kidney and no backup.

“If I was told that donating a kidney was going to shorten my life by five years, I still wouldn't have hesitated. It was for family, and this is what we do for family,” Drew said. “She's not just my mom, she's a community caretaker. It's my kids' grandmother — their Gigi. As a society, we need more of a mindset of 'Do it for others regardless of the impact for you.' That's my mentality.”

He did have one crucial question for the doctors: Could he still drink Monster Zero Sugar energy drinks? Yes, they told him, though he has cut back from two or three to just one a day - arguably a good idea aside from only having one kidney.

The two pairs recently met at the business owned by Kip Barefoot, Tea with Kip. From left to right: Jessica Corey with Drew Barefoot, and Kip Barefoot with Lana Castle (Contributed photo)

For Kip, the owner of the Tea With Kip tearoom in Midlothian, Virginia, life is “perfectly normal,” she said. “There's nothing really that I can't do.” She continues to run her business and host teas for loyal patrons at her tearoom.

Earlier this year, Kip and Drew hosted their new pair of friends from the kidney swap, Lana and Jessica, at the tearoom. They're planning another meeting soon.

In sharing her own story, a handful of others in the Richmond area who needed a kidney have reached out to her for help. Kip took to Facebook Live and encouraged her faithful network of followers to consider becoming living donors.

“The biggest change for me is the gratitude — that someone is so kind and willing enough to give part of themselves to someone else,” Kip said. “Even if you aren't a match for the person you are testing for, open up to donating it to someone else, because you don't know whose life you're going to change. To be given the opportunity to make more memories with my grandchildren, and to just live each day and have the quality of life I do, it's astounding.”

.jpg)